BUDOWLE & OBIEKTY Public utility buildings

Colosseum – an imperial response to a social need

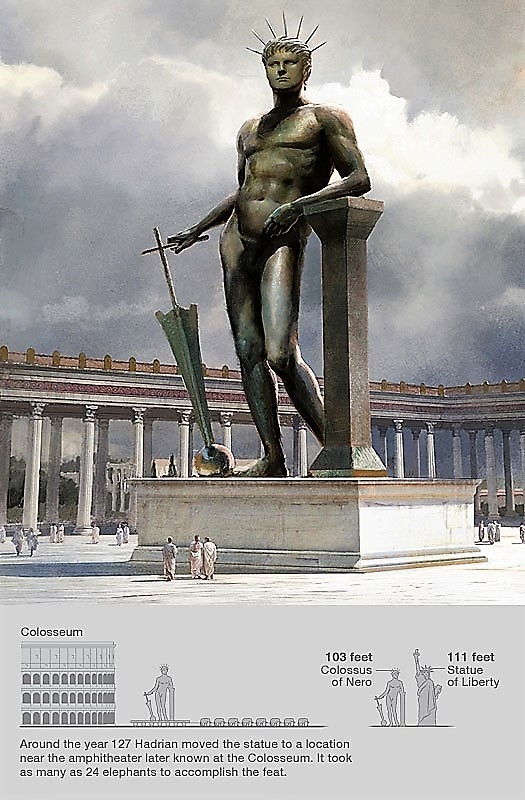

The name Colosseum with which we generally associate this splendid building, came about because of the name of the enormous sculpture of Emperor Nero, known as the colossus, which was found nearby and which was not demolished after his death. It was simply transformed into a monument devoted to the Sun God Sol. It stood there at least until the IV century.

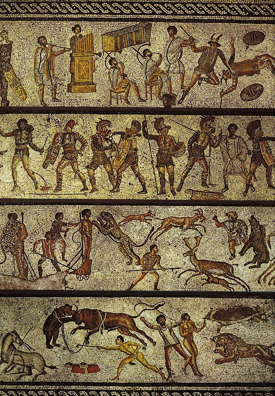

After the power in Rome was taken over by the emperors from the new Flavian dynasty (Vespasian and his son Titus), searching for the best way to find favor with its inhabitants, they did not forget about the exaggerated, almost megalomaniacal actions of their predecessor, Nero. In contrast to him, they desired to create something spectacular for the Romans themselves. They also remembered that during the fire in 64 A.D., the amphitheatre (which had existed since 29 B.C.) on the Field of Mars was destroyed and while Nero did have it rebuilt, it was only out of wood, directing his attention to planning his own palace complex. Vespasian and Titus refilling the imperia treasury with loot from the Jewish-Roman War in 70 A.D. and the valuables stolen from the Jerusalem Temple, decided to give the whole area of Nero’s palace - Domus Aurea (Golden House) along with the gardens, to the people of Rome. In a valley between Palatine and Esquiline Hills they founded a monumental amphitheatre – a place for special performances. In the next centuries it served subsequent emperors to garner support, strengthen their own image and appeal to the tastes of sensation-seeking Romans. The structure was designed for animal combat (venationes), for killing animals in various ways, for shows of animal

training, as well as gladiator fights, both against animals and against each other.

Was there a need for such type of fights? Did the Flavians gauge the desires of their people correctly? Most likely yes. Gladiator fights had special significance for the Romans – it is often forgotten that it was not (at least at the beginning) a pure bloodbath and brutal entertainment. At the times of the Republic, prisoners were still forced to honor their comrades who fell in battle, in this way. The first organized gladiator bouts took place at Forum Boarium as early as the mid-III century B.C.

Initially arenas were constructed out of wood and funded by senators and politicians, including Julius Caesar or Pompeii the Great. Subsequent emperors in the following centuries, did not give up using this method of achieving popular support, even Nero, although he did treat it with skepticism bordering on scorn. He was not alone – the fact cannot be hidden that, among the intellectual elites of the I and II century the games were criticized. Seneca, Nero’s teacher described them in such a way: “Man is a sacred thing for humanity, but today he is killed in the arena for sport.” Nevertheless, the brutal games were to a greater of lesser degree supported and financed by all emperors, while all free citizens of the city were able to watch them for free. The victors of these battles enjoyed great popularity among the audiences, similar to that which today accompanies football players. They often earned fortunes, while their names were honored and venerated in a similar way to the competitors who took part in chariot races. Furthermore, they seldom found death at the arena, while veterans could even count on their freedom and peaceful old age. Their popularity was such and the devotion of the people so great that even Emperor Commodus himself, the son of Marcus Aurelius wanted to experience them. He sought appreciation and fame, not as Nero had in poetry and music, but in subduing, or more appropriately – in killing wild animals, at the outrage of the Senate and the Roman aristocracy – who believed that such type of behavior was unfit for an emperor.

Death on the arena did await criminals. As a form of public warning slaves were generally sentenced to this cruel death. It was sanctioned by the damnatio ad bestias formula of death, meaning being torn apart by wild animals. This had its moral significance – you acted as a beast, then you shall die as a beast. Depending on the crime, the convicts were able to either carry weapons or not. They also fought among one another (damnatio ad ferrum). In this case, they could count upon being found innocent by the audience, if they exhibited courage and bravery. However, their death was most often intertwined into popular, mythical or theatrical spectacles. Researches however, do not agree on whether such executions did actually take place in the Colosseum. They do agree on the fact that this was a place of executions of Christians.

The construction of the elliptical amphitheatre was started in the year 72 A.D. and completed eight years later. It boasted a perimeter of 526 meters, four floors and was 49 meters high. The walls were made out of tuft or bricks and covered with travertine. Each of the visible external niches was filled with a statue. The uppermost floor was topped off by a wall, on which sail canvas was placed in order to protect the audience from the sun. And it was a varied audience indeed. A specially secured imperial box was located on the shorter side of the amphitheatre, a location also used by the Vestals, senators and priests. The lower stands were destined for dignitaries and the wealthy, the middle for patricians, the lower for the populace. In total the spectacle could have been watched by 50 thousand spectators. In order to facilitate communication, an ingenious way of movement was developed, today used in the construction of stadiums, using a system of ramps, corridors and stairs, made in such a way as to allow one to reach his designated and well-marked seat in a matter of few minutes, completely collision-free. 80 entrances placed around the arena also served this purpose, while in order to protect the spectators from wild animals, it was separated with a sort of a water channel.

Emperor Vespasian completed the construction up to the second story, but the official opening of the amphitheatre was inaugurated in the year 80 A.D., by his second son – Emperor Domitian. The festivities connected with it were indeed imposing. The games lasted one hundered days. Nearly 5 thousand animals were slaughtered, gladiator fights took place – in pairs and groups, the audience received gifts, while the whole was completed by a naval battle, staged in the arena filled with water.

Gradually the rooms under the arena were expanded, serving as a storage for equipment and to house wild animals. At that time the staging of naval battles, which required filling the arena with water, became impossible.

The following centuries brought about an increase in the amount of animals murdered and gladiators forced to do battle, while all of the hill with the amphitheatre (Pincio Hill) was day and night filled with the roaring and howling of animals destined to die, which were kept there prior to the games.

The procedure of killing animals and people at the arena lasted until the year 326, when Emperor Constantine the Great forbade such types of spectacles, while convicts were sent to labor at the rock quarries. However, the deeply rooted tradition prevailed. Under the pressure of the Roman populace, he was forced to reestablish the games, just as his successors would do. A definite end was put to gladiator fights one hundered years later, letting only animals fight each other. This tradition lasted longer than the empire itself, despite the fact that an earthquake and lack of conservation of the Colosseum caused part of the stands to be closed. Even a lack of emperor and the process of Christianization could not eliminate the need for such type of entertainment. The last hunt for wild animals, or more appropriately a chase, was organized during the reign of the Ostrogoth King Theodoric the Great by Roman consuls (in 519 and 523 A.D.), since Romans required from them not only bread, but games as well.

The following centuries brought about a slow ruin of the Colosseum. It arcades were since the IX century built over, using them for warehouses, stables, or apartments, while part of the structure was occupied by the Frangipani family in order to raise one of its fortresses there. In the XIV century bull fights were organized in the amphitheatre, until another earthquake seriously damaged the building. From that time it served as a “rock quarry” a place to obtain materials for the newly built Roman palaces and churches. Subsequent centuries – the times of Renaissance and Baroque and their fascination with antiquity – did not bring about any change: both the popes, as well as outstanding Roman families, used the Colosseum as a building material for their private residences (Palazzo Venezia, Palazzo Farnese). The slow devastation as well as following cataclysms would have indefinitely removed it from the face of the Earth, if not for Pope Benedict XIV, who in the middle of the XVIII century announced that anyone who would further demolish the building would be excommunicated. At that time stations of the cross were built inside, while in the middle a cross was erected to commemorate Christian martyrs, who reportedly died here. This saved the building from utter demolition, which was experienced by Circus Maximus. Since that time every Good Friday the Colosseum is witness to a solemn celebration of the Stations of the Cross, in which the pope himself participates.

In the XIX century, the conservation of the structure was begun, while in the XX century Benito Mussolini, a great admirer of antique art, created the proper setting for it and for himself. He demolished everything that was located around and built and the imposing via dell’Impero (via dei Fori Imperiali) – a promenade between the Colosseum and his residence in the Palazzo Venezia, appropriate for military marches and parades of Fascist formations.

Może zainteresuje Cię również

Emperor Titus (39–81) – the conqueror of Jerusalem and lover of Berenice

Zgodnie z art. 13 ust. 1 i ust. 2 rozporządzenia Parlamentu Europejskiego i Rady (UE) 2016/679 z 27 kwietnia 2016 r. w sprawie ochrony osób fizycznych w związku z przetwarzaniem danych osobowych i w sprawie swobodnego przepływu takich danych oraz uchylenia dyrektywy 95/46/WE (RODO), informujemy, że Administratorem Pani/Pana danych osobowych jest firma: Econ-sk GmbH, Billbrookdeich 103, 22113 Hamburg, Niemcy

Przetwarzanie Pani/Pana danych osobowych będzie się odbywać na podstawie art. 6 RODO i w celu marketingowym Administrator powołuje się na prawnie uzasadniony interes, którym jest zbieranie danych statystycznych i analizowanie ruchu na stronie internetowej. Podanie danych osobowych na stronie internetowej http://roma-nonpertutti.com/ jest dobrowolne.